The Clapham Society Local History Series — 16

The Case of Dr. Ward

by Derrick Johnson

This article first appeared in the South London Press on 3 February 2017

(Entitled: ‘The box that created today’s garden’)

It may be difficult to believe that this strange piece of Victorian furniture changed the face of horticulture and the plants which we have in our gardens. In the 18th and first half of the 19th centuries plant hunters scoured the world for beautiful and interesting plants but their attempts to bring them back to our shores as live specimens were largely in vain. In the days of transport by sailing ships nearly all of their collections succumbed to salt winds, changes of temperature, lack of fresh water and proper attention. All of this was to change.

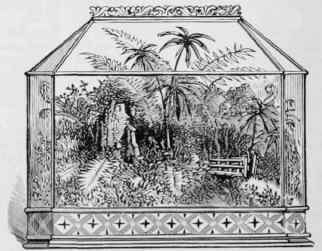

A London doctor Dr Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward (1791 – 1868) tried to grow ferns in his garden in Wellclose Square in the London docks. However, due to the smoky atmosphere none of them survived and he gave up in despair. But Dr Ward was also an entomologist and one day in 1830, wishing to observe the development of a hawk moth, he buried the chrysalis in moist earth in a sealed bottle. A few days later he noticed that water vapour had condensed and run down the sides of the bottle thus keeping the amount of moisture constant. Before the moth emerged he was surprised to note that a fern had germinated in the bottle where it flourished for four years without additional water or the cover being removed. He deduced that the fern needed a clean, humid atmosphere and protection from draughts. To prove his theory he constructed numerous glass fern cases, like miniature greenhouses, in which he was able to grow a wide range of ferns and other plants. One of his successes was the Killarney fern. This is one of the filmy ferns that normally grow in caves where the atmosphere is constantly moist. Its fronds are almost transparent and it is so delicate that they shrivel in dry air. Ferns were very fashionable in Victorian times and soon so called Wardian Cases in increasingly elaborate forms, like the one illustrated, became a feature of drawing rooms.

It was the adoption of this seemingly simple principle to transporting plants around the world in closed glass containers needing little or no attention that enabled a huge range of plants to be rapidly introduced into our gardens without the need to go through the slow and often difficult process of raising them from seed.

In 1838 Ward shipped two custom built cases filled with native British ferns and grasses to Sydney in Australia. After six months on the high seas they arrived with all the plants alive and flourishing. The cases were cleared out and filled with a number of Australian native species which had proved impossible to transport in the past. After an eight-month storm tossed journey they arrived in London in good health. Orchids, tea and rubber were some of the commercial plants which were distributed in this way.

The Wardian Case went out of fashion and original examples are difficult to find, even in antique shops. However, it is currently experiencing a revival. With so many people living in rented accommodation with no outside space indoor gardening has become popular and at last November’s Royal Horticultural Society Urban Garden Show several modern examples were available and proving popular with younger visitors. What could be more convenient than a garden which you can take with you when you move?

Dr Ward later lived at what is now 397 Clapham Road (formerly Clapham Rise) close to Clapham North Station in an attractive double fronted house built about 1825 and it was here that he kept his ‘neatly mounted herbarium’ containing 25,000 specimens. Sadly the house is now in a poor state of repair. We can only hope that it will be restored and perhaps eventually receive a blue plaque to commemorate a distinguished scientist.