The Clapham Society Local History Series — 2

Ada Alice Pullan (Dorothy Dene)

by David Perkin

A talk given at the Clapham Society’s meeting on 20 November 2001

The Road to Clapham

This is the story of a working class girl from Victorian Lambeth who moved to Clapham in search of a better life, as one does.

In his book Clapham Saints and Sinners the historian Eric Smith devotes four short paragraphs to Ada. He tells us that Ada and her nine brothers and sisters were all born in Forty Cottage, New Cross and that they moved from there to Clapham. He is wrong, but so is the source he uses. What actually happened?

The first step was to find Forty Cottage. I booked sessions with the Local Archives in Lewisham, Lambeth, Wandsworth and Hammersmith, and rang up those at Southwark. They very kindly got out large-scale maps, rate books and census returns for me. We looked for where Forty Cottage should have been, in what was then New Cross Road, two similar adjoining properties, one of which we calculated was Forty Cottage. The cottage ended its days as a second-hand bookshop before it was demolished in 1904 to make way for the new Edwardian Lewisham Town Hall. The rate book told us that it was rated at £20 per annum — a not inconsiderable rate for the time, especially as the neighbouring properties were rated at £6. The next step was the census return for 1861. We found the address, now identified as Forty Cottage. But the householder is a Mr Eagle a millwright, with wife, Dorothy, four children (two boys who are apprentice engineers, and two girls one of whom is another Dorothy and a dressmaker) and a boarder who is a draughtsman. Then a line is drawn across. Where is Ada? Then I noticed below the line four more names, Abraham Pullan, an engineer born in Yorkshire with his wife Sarah born in Durham, with two children, Thomas and Ada. And Sarah’s maiden name was Eagle. Perhaps one can deduce from all this that the Eagle family came to South London from Durham and settled in Forty Cottage, a working class family but with prospects, the father a millwright with two sons already apprenticed as engineers. When his eldest daughter married another engineer he made room for them in Forty Cottage. With himself, two sons and a son-in-law all earning and in trades soon to become professions he could well afford the £20 rates.

We looked ahead to the next census. The Pullans have left, but not for Clapham. After some searching we found them. Abraham with his wife Sarah and Thomas and Ada have moved just a few doors away to No. 306. But now they have five more children, the youngest, another Dorothy again, only a year old. By now Thomas is 12 and Ada 10 so it is worth considering what sort of education they might have had. Forster’s famous Education Act providing elementary education had only just been passed in 1870, but a few streets away is a fine new Victorian gothic church, built in the 1850s carved out of the old parish of St Paul’s Deptford and next to it a fine new National School, one of those built by the Church of England for its own children. The Pullans have three more children born here bringing the total to ten. But by the next census in 1881 they have moved again, but still not to Clapham. They have moved to 23 Station Road Lambeth (probably the one in Loughborough Junction).

But not all of them. The elder children have moved and Thomas is now the head of household aged 23 and proudly described as a civil engineer. His sister our Ada is also here now 21 and so are six other of the brothers and sisters. But the parents are missing and so are two children. What has happened?

We learn from the memoirs of Mrs Russell Barrington that there was a disaster for the family in 1877. In that year the tenth child, Samuel, was born, but in the process Sarah damaged her spinal column and became a helpless invalid. In the same year the daughter Dorothy now aged 8, died, and finally the father Abraham deserted the family and was never seen again. Some time after 1877 we have to deduce that Thomas moved with his eldest sister Ada to Station Road to look after the dependent children (Samuel the youngest was only four in 1881). But someone had to look after the mother who died also in 1881. Eric Smith records that she died in Thomas’s house in Camberwell. Did Thomas have a house in Camberwell with his mother and did he only move to Station Road with his sister after her death and before the census return? And where was the second youngest son Henry who would have been 19 at this date? Room for more investigation, but for now, it is worth establishing that although Ada was a working class girl, the family was respectable, and one might say ‘upwardly mobile’. The men in the family in particular were all in jobs which soon were to acquire professional status, gained by passing qualifying examinations. But what of the girls? This is Ada’s story.

Clapham — Gateway to Fame and Fortune

We know that Ada moved to 83 The Chase (now 103) and lived there for most of the 1880s. The census return for 1881, of course, shows her in Station Road, but in the same year the census return for The Chase shows No. 83 to be empty. Perhaps she moved there later that year. By the 1891 Census the Pullans have clearly left. The only official evidence we have that the Pullans were there at all is to be found in the list of voters. Women could not vote at the time so the only name recorded is Thomas Pullan, voter in 1881 electors’ list.

But what is Ada doing? In contrast to her brothers who by now could advance their status by becoming qualified engineers the prospects for a girl were more hazardous. Apart from marriage and the upbringing of numerous children domestic service was the only respectable opportunity available. A generation too early for escape to other respectable work through the invention of the typewriter the only other opportunities were fraught with danger and the calamitous risk of irreparable loss of respectability. Was she a dressmaker like one of her aunts? Or was she a domestic servant? Ada describes herself aged 21 in the 1881 Census as an art student, but we know from memoirs that she was working from 1879, presumably to help with the expense of looking after her brothers and sisters. She was working for an artist, Louise Starr Canziani, in Kensington. It is just possible that she was learning how to mix paints and the rules of perspective, but in fact she was an artist’s model.

The redoubtable Mrs Barrington, an artist herself, recorded in her memoirs ‘a young girl with a lovely white face, dressed in deepest black, evidently a model, standing on the doorstep of the Holland Park Studios’ and reported this to Sir Frederick Leighton, who lived in his splendid house opposite. Leighton took her and introduced her to Watts. Both of them were attracted by her delicate complexion, ‘a clouded pallor, with a hint somewhere of a lovely shell-pink’. Evidently Watts was more successful at portraying it. Others remarked on her ‘pretty brown eyes, with long, curly lashes, delicately chiselled features, and an aureole of light golden hair.’ There are some early photographs of her in the Theatre Museum which show her looking up coyly through her eyelashes, a look which the curator told me is now called the Princess Diana look.

Please click images to see a larger version and click outside the image to return.

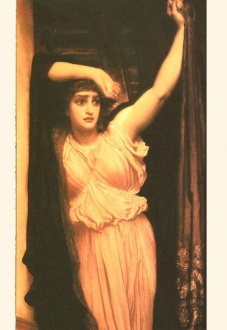

Fig. 1

Portrait of Dorothy Dene, 1884

There is a charming portrait of her in Leighton House, called Bianca, in which she looks much younger than her age. But by now Ada’s sisters were hoping to copy her, and in fact Leighton used them more frequently in his paintings. At this time Leighton was at the height of his fame, newly elected President of the Royal Academy, but frankly his paintings were rather ordinary dull stuff, pretty and sentimental, with coy titles like Kittens, for which Lena, Ada’s youngest sister modelled. They sold very well, of course. Still in sentimental mode Leighton used Ada as his model for Wandering in a trance of sober thought. (Fig.1)

Fig. 2

Antigone

Leighton managed to make Ada look older sideways and younger full face. Notice that determined chin. Ada had no intention of remaining in the somewhat dubious occupation of artist’s model. She wanted to become an actress. She had a gift for striking dramatic expressive poses. It is at this stage that Ada becomes the inspiration for Leighton’s new style of painting, and Leighton becomes the indispensable supporter of Ada’s ambitions as an actress. Leighton was one of the leaders of the neo classical movement and now Ada becomes the principal model for his grand, luscious, luxurious displays of classical scenes. An early example of Ada’s dramatic poses is Antigone. (Fig. 2)

Fig. 3

Last watch of Hero

By now Ada decides she needs a professional name, as a model but more particularly as the actress she hopes to become. From this time she is known as Dorothy Dene.In 1887 she posed in The Last Watch of Hero (Fig. 3) anxiously waiting the return of her lover Leander, her face a wonderful mixture of fear and hope.

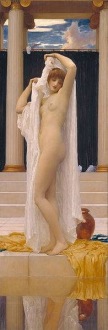

Fig. 4

The Bath of Psyche

Tate.org

In 1889 she modelled for The Bath of Psyche (Fig. 4) Currently she is all over London on posters, her delicious charms confronting you on the escalator of the underground, and she may be purchased for £7.99 as a coffee mug, or more cheaply as scented soap, scented candle, pin, as a disposable camera at the Tate Britain shop. In Victorian England, however, the nude was suspect, and it was Leighton above all who made the nude respectable, or rather he painted the acceptable example of the pure nude, Classical woman. But in society the artist’s model was a different matter.

Fig. 5

The Garden of the Hesperides

Liverpool Museums.org

Dorothy continued to model for Leighton, until his death, perhaps the most decorative and luxurious painting being The Garden of the Hesperides (Fig. 5) modelled by Dorothy when she had moved to her new flat in West Kensington. And of course there was the famous Flaming June, which Eric Smith suggests was modelled by Dorothy, painted by Leighton and exhibited just before his death. But what of Dorothy’s acting career?

Kensington. The Ladies in Waiting

The 1891 Census shows that the first resident and head of the household of No. 10 Avonmore Mansions, a newly built block of flats, was a Miss Dorothy Dene — no longer Ada Pullan. (Interestingly her sisters and youngest brother living with her had to change their names to Dene as well). Once describing herself as an art student she now declares herself not as artist’s model but firmly as an actress, as does her sister Hetty. The other two sisters who were certainly models are simply described as without occupation. And she now has a resident domestic servant. She has arrived. But has she arrived as an actress?

When Leighton’s painting Wandering in a Trance of Sober Thought was reviewed the unfortunate reviewer got the model’s name wrong. Rather pompously Leighton corrected him. ‘I cannot of course contradict such a trifle myself — I who never rush into print — but if you care of your own reason and knowledge to correct the error in your gossip column it will perhaps be as well that the truth which does not always prevail should be made known’. Of course he corrected it and added that Miss Dorothy Dene was about to make her London debut.

It was a matinee performance at the Prince’s Theatre (the matinee fashion was of some songs and recitations followed after the interval by the more substantial part such as a short play, on this occasion de Bainville’s Gringoire with Norman Forbes in the lead and Dorothy playing the part of Louise). Leighton was present — he supported all Dorothy’s acting — with friends, and recorded ‘Poor Dorothy was paralysed with fear yesterday, but I hope intelligent people will have seen through that.’ I discovered with the programme a review of the performance at the Theatre Museum.

‘The matinee nuisance flourishes in spite of all remonstrance. Seldom indeed has such palpably indulged acting been so popular as it is now. Mr Norman Forbes… a young actor with Miss Dorothy Dene and others, has been vigorously applauded by assembled friends….. . Mr Norman Forbes is not actor enough for Gringoire as yet… Miss So and So who has just stepped out of the schoolroom… there is no law to prevent…but should such a youthful effort demand serious criticism? Such actors and actresses can practise in private…’.

After this less than enthusiastic review Dorothy went on tour in the West Country. Here she played a mad woman in a popular play Called Back. Leighton encouraged her to visit Bedlam to study the paroxysms of the patients, and she played the part with astonishing accuracy as a result. Back in London she joined Beerbohm Tree’s production of The Ballad Monger at the Haymarket and then went off on another tour. Her big moment came in 1886 when a charity event was organised in support of two new London colleges. All the best people gave their support for what was obviously meant to be a high-class production — a performance of Professor Wair’s translation of The Oresteia by Aeschylus. The very best of the fashionable artists designed for it — Watts, Poynter and Walter Crane, and of course, Sir Frederick Leighton, as a sort of presiding genius of classicism, beamed down. And a very fashionable audience attended, from the Prince and Princess of Wales down. But the acting …. ‘Boredom, polite but unmistakable was writ large. The play was tedious and the players hopelessly incompetent’. Punch found the text tedious and the cast too weak for criticism. Only once did the play come alive, when Cassandra delivered her warning to Troy. It was an ideal part for Dorothy, who played it for all it was worth. ‘A young lady who could be heard, who was not in the least embarrassée de sa personne, who showed herself, moreover, in her one declamatory scene, possessed of considerable dramatic power’. Even Punch excepted her: ‘She put life and force into the captive prophetess, casting aside the modern manner, and giving us tragedy as it should be acted and poetry as it should be spoken. The delighted audience, released from an imprisonment of dullness, broke out like schoolboys … Miss Dorothy Dene electrified them with her dramatic warning.’ As a result, more engagements followed, at the Olympia where she played in Sheridan’s School for Scandal, at the Prince’s where she appeared in Forget-me-not and The Noble Vagabond. In 1890 she played in Frank Benson’s company at the Globe in A Midsummer Night’s Dream — but looking at the programmes at the Theatre Museum it was only for one performance when she took over Kate Rowles’ part as Helena.

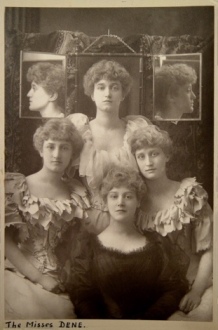

The Pullan (Dene) Sisters

Maas Gallery

Still, she went on tour with the company to Manchester, all the time eagerly supported by Leighton. ‘Though not at present in an engagement here’ he wrote reprovingly to someone who had mistaken her for an amateur, ‘she is well known as a leading lady and very highly thought of by those who appreciate poetic work’. The truth was however, that she would not have got so far without Leighton’s constant support. Her lack of sophistication, her downright South London manners were a delight to Leighton, who regularly visited the Pullan girls both in The Chase and in Kensington. The President of the Royal Academy, with all his official functions, was a lonely bachelor who said ‘I go to see them when I want to let my back hair down and get off the stilts’. He organised a photo of The Pullan Sisters, probably at The Chase. (Fig. 6)

In 1896 Leighton died, a month after being made a peer. He provided handsomely for Dorothy and her sisters in his will. Dorothy had one more performance in April, at the Metropole in Camberwell. After the matinee interval she performed in extracts from Shakespeare’s plays as part of a week of celebration.

I viewed the programme at the Theatre Museum. There was Romeo and Juliet Act 2, with Henry Irving as Romeo and Dorothy Dene as Juliet. With only two performers this must have been Act 2 Scene 2, the famous balcony scene. Then followed the forest scenes from As You Like It, in which Dorothy Dene did not appear, but her youngest sister, Lena appeared as Helena. Eric Smith says she played Ophelia (his source says Juliet and Ophelia). Hamlet is indeed the last item on the programme, but it is the closet scene, in which the only actors are Polonius, the Queen, Hamlet and a ghost. Dorothy doesn’t appear as any of them. Her performance as Juliet received favourable notices, but without Leighton’s powerful influence she did not receive any further contracts. She died of peritonitis on 27 Jan 1899 aged 39, three years after Leighton.

POSTSCRIPT. Enter George Bernard Shaw

In the late 1870s, just about the time when Leighton first met Dorothy, Sir Coutts Lindsay opened The Grosvenor Gallery in New Bond Street, as a rival to the somewhat staid Royal Academy and as an opportunity to exhibit a broad range of contemporary painting. There were displays from the leading artists of the time, even Leighton, conservative President of the Royal Academy. He managed as always to remain friends with artists who scoffed at his style, and contributed, as did his old friend Edward Burne-Jones, who between 1875-8 was completing a series of four paintings on the theme of Pygmalion, the artist who falls in love with his own statue and brings her to life. They can be seen at the current exhibition at the Tate Britain, and represent the acceptable Victorian nude, the pure woman, made acceptable by her classical pose. Both Leighton and Shaw, who moved in the same fashionable circles, are curious examples of attempts to transform the lifeless model into a new perfection. It is worth comparing them.

1. Eliza Doolittle has a problem. “I ain’t done nothing wrong…I’ve a right to sell flowers if I keep off the kerb. I’m a respectable girl….you dunno what it means to me. They’ll take away my character and drive me on the streets for speaking to a gentleman…”

Dorothy had started a very successful career as a model. Most models came from the working class, and though they were mostly eminently virtuous, they could never escape the taint of being persons who posed unchaperoned alone with a man scantily dressed or worse, and were not received in polite society. We have already seen how carefully Dorothy avoided calling herself a model.

2. The model speaks. “You see this creature with her kerbstone English, the English that will keep her in the gutter to the end of her days… Well, Sir, in three months I could pass that girl off as a Duchess at an Ambassador’s garden party, I could even get her a place as a lady’s maid or a shop assistant, which requires better English”. When Leighton first heard of Dorothy’s desire to act he poured scorn on the idea. “Impossible. With that voice? How could she go on the stage?” But he paid for her to have lessons in drama and elocution under Mrs Dalla Glyn and Mrs Chippendale.

3. The model enters society. At Mrs Higgins’s ‘At Home’ she rebukes her son. “You have to consider not only how a girl pronounces, but what she pronounces”. Shaw makes a great joke of this, with Eliza shockingly speaking her mind and uttering the forbidden word for the first time on the modern stage, and the social snobs deciding that this must be the latest fashion. Her adoring Freddie says “the new smart talk. You do it so well.” But in reality life is harsher.

Leighton deliberately got Dorothy invitations to functions she could not have attended as a model. Soon sharp pens were writing. ‘Dorothy… belied her beauty by talking a deal of nonsense in the fashionable slang of the day’. Eyebrows were raised in society at large.

4. The model is left adrift. “What is to be done with her afterwards?” Mrs Higgins asks.

“Now you are free and can do what you like.”

“What am I free for? What have you left me fit for? Where am I to go?”

“You might marry.””I sold flowers. I didn’t sell myself. Now you’ve made a lady of me I’m not fit to sell anything else.”

As we know, Shaw leaves the question of whether Eliza marries Freddie tantalisingly open in his play. But real life again is harsher. Dorothy did in fact have a romance. She was engaged to marry Anthony Crane, son of Sir Walter Crane, the eminent painter and illustrator who became first Principal of the Royal College of Art (who was one of the set designers for her appearance as Cassandra and no doubt Dorothy encountered Anthony there). But she hadn’t reckoned with Mrs Crane. Mrs Crane objected to female models, and especially in her husband’s studio — he had to make do with male models and imagine the rest. So Dorothy was doomed and the engagement was broken off. Even Leighton couldn’t get her through the social barrier. He confided to the more sympathetic wife of another artist friend, Mrs Watts ‘my interest in her has been turned to her disadvantage’.

Was Dorothy a prototype for Eliza? In the index of Michael Holroyd’s monumental biography of GBS there is no reference at all to her, but we know that GBS knew Dorothy. He reviewed her. In his collected reviews in Our theatre in the Nineties he writes ‘I was late for Miss Dorothy Dene’s Juliet. This I greatly regretted. Miss Dene was a young actress who had not the painted show of beauty which was so common on the stage, and so useless, but that honest reality of it which is so useful to painters. Her speech showed unusual signs of thoughtful calculation. She had plastic grace, she took herself and her profession seriously, and her appearances in leading roles were not unpopular. The mystery is, what became of her? Did the studio instantly reclaim its adored model? Did she fall into the abyss of opulent matrimony? Did she demand impossible terms? Or were the managers obdurate in their belief that there is only one safe sort of actress — the woman who is all susceptibility and no brains.’

I rest my case.

APPENDIX 1 Flaming June is discovered in Clapham

Fig. 7

Flaming June

Sometime in 1962 ‘some workmen were demolishing a large house on Clapham Common when they ripped out a false panel over a chimney piece to get at the brickwork, when they found a picture, frame and all, behind the panel. Bernard [Nevill] immediately imagined that someone in the 1920s or 30s — “some bright young things couldn’t stand this monstrous, garish painting, so they put a panel over it”‘. This story seems to me so unlikely that I quote verbatim from Jeremy Maas’s account of a discovery by Professor Bernard Nevill of a Victorian painting in a framing shop owned by a Pole in Lavender Hill. After all, if you have a picture you don’t like why go to this effort? Why not simply put it in the attic? However, somehow the workman had found the picture, decided that the frame was worth a bob or two and made a quick sale with a demolition story at the local frame shop. Professor Bernard Nevill had visited the shop looking for Pre-Raphaelite paintings. Picture framers are good hunting grounds for speculators. The framers only want the frames, the speculators want bargains, unfashionable paintings which might gain value later on. In the 1960s Victorian art was at a low ebb. Derided by the critics, it could hardly be sold at all. This picture, which Bernard Nevill had noticed had a label on the back indicating that Lord Leighton was the painter, was on offer for £60. But at that time ‘Bernard was strapped for cash, having only that morning received a very nasty letter from his bank manager’, so he didn’t buy it. Strangely, another, much younger connoisseur, a schoolboy of fourteen was also in the area at the time, saw a frame, by now detached and going for £65 and the picture lying on its side at the back of the shop priced separately at £50. It was, of course, Flaming June (Fig. 7)

The boy rushed back to his father to borrow the cash but it was decided that their South Kensington flat was too small to hang it. The father was at that time a Professor of Music and also organist and choirmaster at All Saints Margaret Street, a high Anglican Victorian gothic church by Butterfield famous then and now for its elaborate theatrical ceremonial and splendid music. The boy may have acquired his early enthusiasm for the theatre and music here. The father’s name was Dr W S Lloyd Webber and the boy was, of course, Andrew. The picture was eventually sold to a hairdresser, a Mr Demaine of Albemarle St. He sold it to a Colonel Freddie Beddington, who had at one time been a pupil of Leighton’s friend Poynter. Having no room for it he offered it to Jeremy Maas who had just opened up a shop hoping to make money by reviving a taste for Victorian pictures. The asking price was now £1000 and Jeremy Maas could hardly afford the investment. But he risked all, bought it, and watched the days pass without a sale, till in June 1963, in a heat wave, The Evening Standard came out with a headline ‘Flaming June’. Within days a Mr Taylor viewed it and bought it on behalf of Mr Luis A Ferre, Governor of Puerto Rico, for his Museo de Arte de Ponce. And there it is today, probably the best known example of high Victorian Art, known there as ‘The Mona Lisa of the Western Hemisphere’.

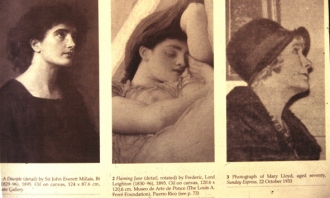

APPENDIX TWO. Flaming June reappears in Clapham, but does Dorothy?

In the early 1930s an enterprising young reporter from the Sunday Express encountered a frail old lady living in much reduced circumstances in a garret in Kensington, and invited her to tell her story. Her name was Mary Lloyd. She had been born in Shropshire, the daughter of a prosperous county squire, but when her father became bankrupt was left destitute, trained for nothing, like most upper middle class girls, except marriage within her class. Without money she was no longer eligible so she journeyed to London to seek employment. She chose to become a model, and like Dorothy Dene, was taken up by the leading established painters of the day. Unlike Dorothy, however, she had demeaned herself by entering the not quite respectable working class world of modelling because she needed money and remained reclusive, hoping nobody would realise she was the daughter of a county squire, while Dorothy had moved into modelling hoping to use it as a gateway to becoming an actress.

Mary Lloyd began modelling for John Everett Millais ‘who was captivated by her beauty’, and then for Laurence Alma Tadema, Sir Edward Burne-Jones, Ford Maddox Brown and William Holman Hunt. Leighton used her often, and if you go to St Paul’s Cathedral you will see her modelled in bronze on one of the corners of Leighton’s tomb in the North Aisle of the nave. But when she started modelling these leading painters were all elderly and when they died she was left destitute again. The story was good enough to print and it duly appeared on Sunday 22 October 1933 under the heading ‘The story of Mary Lloyd who had the face of an angel but outlived her luck’.

Fig. 8

Leighton’s Studio

English Heritage NMR

And she was forgotten again, till the Leighton centenary exhibition, when an art historian, Martin Postle, looking at an old photograph of Leighton’s studio, suddenly noticed something. There are many photographs of Leighton’s studio usually showing Leighton himself posing with a brush or two. But this photograph was taken after his death, and it shows Leighton’s Studio (Fig. 8) with the paintings left unsold when Leighton died. If you look at the main painting on the right, you will see that it is Flaming June, in the frame Leighton designed for it (the one the workman thought was probably worth a bob or two). Now Leighton was very particular about his frames, often choosing a Greek style portico to heighten the impression of drawing you into the subject, as in Flaming June. But if you look three pictures to the left you see a very similar frame, again a Greek style portico, this time drawing you into another subject, Lachrymae. Both subjects, Flaming June and Lachrymae, are stylised emotions set in the Greek background, a Greek woman relaxing in the heat of summer, and a Greek woman mourning by her loved one’s funeral urn. We know that the model for Lachrymae is Mary Lloyd. And she is the model for at least one more painting in the photograph. Is it just possible …….?

Fig. 9

Flaming June & Marie Lloyd

Apollo Magazine

Look at this comparison made by Martin Postle, Flaming June and Mary Lloyd compared (Fig. 9). The woman on the right is Mary Lloyd, now aged about seventy, taken at the time of the Sunday Express article. The woman on the left is also Mary Lloyd at the same date as the model for Flaming June in the centre, turned sideways for comparison. Do you see a similarity, sufficient to declare that the model for Flaming June is Mary Lloyd?

Ladies and gentlemen I present Ada Pullan, a Victorian working class girl who came to Clapham to seek fame and fortune. She achieved much, but only within the class boundaries set by Victorian society. Perhaps she wasn’t the model for Flaming June, but surely we can say with confidence that she was a real, historical prototype, Clapham’s own early example of a working class girl who makes good, Clapham’s own Eliza Doolittle

Bibliography

Barrington, Mrs Russell, Life, Letters and Work of Frederick Leighton, 1906

Leighton, Frederick (exhibition catalogue) RA, 1996

Maas, Jeremy, ‘From outcast to Icon’ RA Magazine No 49, Winter 1995

Newell, Christopher, The Art of Lord Leighton, 1990

Ormond, Leonee and Richard, Lord Leighton, 1975

Postle, Martin, ‘Leighton’s Lost Model, The Rediscovery of Mary Lloyd’ Apollo, 1996

(special edition on Leighton and Leighton House)

Shaw, GB, Our Theatre in the Nineties, 1932

Smith, Eric EF, Clapham Saints and Sinners, 1987

Jimenez, Jill Berk (ed), The Dictionary of Artists’ Models, 2001, the first of its kind, appeared too late to be used. It contains excellent brief biographies of Dorothy Dene by Joanna Banham and Mary Lloyd by Cherry Sandover but no new material.