The Clapham Society Local History Series — 20

From Bankruptcy to ‘The Thunderer’

by Anne Wilson

This article first appeared in the South London Press on 24 March 2017

John Walter was born in 1739 and inherited his father’s coal trade business in 1755. He bought 113 Clapham North Side in 1772. In 1773 the rumblings of discontent from the American colonies erupted into the Boston Tea Party and the American War of Independence. It meant financial ruin for John Walter whose experience of bringing coals from Newcastle had led him to become a Lloyd’s shipping insurance underwriter in 1781. The naval powers of Spain, Holland and France supported the colonists and British Atlantic merchant shipping was badly hit. So was the shipping insurance business. John Walter was declared bankrupt in 1782. It was judged to be an honourable bankruptcy so he escaped imprisonment and was allowed to oversee the payment of his own debts through the sale of his Clapham house and his library.

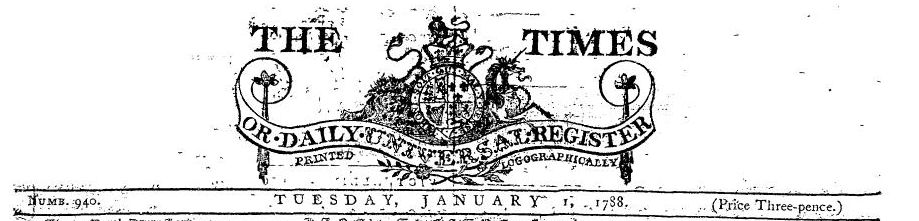

He then turned to another 18th century growth industry, that of printing. In 1782 he bought the patent for a new logographical method of printing whereby whole words were cast rather than individual letters. It was an early version of the idea behind predictive texting. Through his insurance connections he began his printing career by producing the Lloyd’s List but he needed much more grist for his press. On 1 January 1785 he produced the first edition of The Daily Universal Register, the original name of The Times. The bottom of the first page stated that it was,

‘Printed for J. Walter, at the Logographical Press, Printing House Square, near Apothecaries Hall, Blackfriars’.

In his first editorial he announced that he was aiming for a general interest paper. So many other publications catered for very narrow specialist interests such as Parliamentary debates, theatre news, shipping movements, stock market prices and so on. At least the specialist newspapers were assured of a market. John Walter was not so sure that his newspaper would sell. He wrote:

‘To bring out a New Paper at the present day when so many others are already established and confirmed in public opinion, is certainly an arduous undertaking; and no-one can be more fully aware of its difficulties than I am; I nevertheless, entertain very sanguine hopes that the nature of the plan on which this paper be conducted, will ensure it a moderate share at least of public favour.’

His hopes were fulfilled and by 1792 the paper was selling 30.000 copies daily.

The general interests were diverse and provide a wonderful snapshot of the lives, times and concerns of 18th century Londoners. Dancing Tuition, Ham and Cheese supplies, Land and Chattels and Hair Tonics were among the things offered for sale. The news items included bankruptcy orders, coach robberies, commercial contracts, theatre notes, Wellington’s War Dispatches, market reports, extracts from the Lords’ debates and, of course, shipping movements.

On 1 January 1788 he changed the paper’s name to The Times. That first edition carried the following simple announcement:

‘American Philosophers and Philosophy are entitled to the protection of The Times – with Arts and Sciences we shall ever be at peace.’ American politics, of course, were another matter entirely.’

During the 1780s he received £300 a year to publish articles favourable to the Treasury. On 21 February 1789 he printed a Treasury article claiming that the royal dukes had not been exactly overjoyed when the King recovered from a bout of illness. This was judged to be libellous and in November 1789 he was sentenced to one year in prison and a £50 fine. He refused to divulge the source of the libel and was sentenced to further imprisonment and another £20 fine. He complained that he suffered punishment while the Parliamentary Opposition, was printing far more atrocious libels against the King with impunity. But, of course, he could not claim Parliamentary privilege although he might have had a good defence had he revealed his Treasury source.

In 1802 his son John took over production of the newspaper and John Walter senior retired to Teddington. He died on 16 November 1812. He left his assets to be divided among all his children rather than solely to his eldest son. It is thought that relations between father and son were soured as a result. This fact might explain the lack of an obituary and the meagre death notice in The Times of 18 November. It states simply:

DIED On Monday, at Teddington in the 74th year of his age John Walter Esq.