The Clapham Society Local History Series — 29

Two American Visitors to Clapham

by Peter Jefferson Smith

This article first appeared in the South London Press on 25 August 2017

(Entitled: ‘Two very different American visitors to South London’)

In the 1770s, two Americans visited Clapham, one of them a respected if controversial public figure, the other a teenage prodigy.

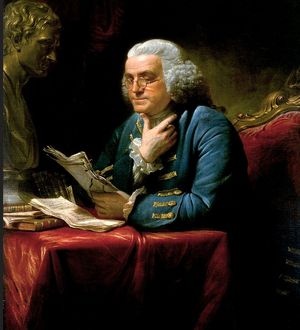

Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin was well known as a writer and politician, and was living in London as representative of the Assembly of Pennsylvania and three others of Britain’s then American colonies. His house in Craven Street, off The Strand, is now a visitor attraction.

Franklin was a keen experimental scientist. On his sea voyages he had noticed that when ships threw out greasy slops, this had the effect of smoothing out the waves. Smoothing the waves with oil was a practice known to the ancient Romans, and seamen thought nothing of it. But Franklin decided to “make some experiment of it”.

Around 1770, he was staying with Christopher Baldwin, a wealthy West Indies plantation owner and merchant, who lived on the West Side of Clapham Common.

“At length being at Clapham,” Franklin wrote, “where there is, on the Common, a large Pond, which I observed to be one Day very rough with the Wind, I fetched out a Cruet of Oil, and dropt a little of it on the Water. … The Oil tho’ not more than a Tea Spoonful produced an instant Calm, over a Space several yards square, which spread amazingly, and extended itself gradually till it reached the Lee Side, making all that Quarter of the Pond, perhaps half an Acre, as smooth as a Looking Glass.”

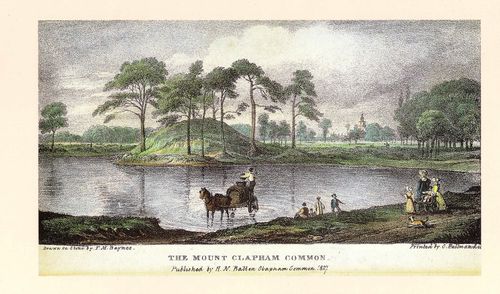

where Franklin might have tried his experiment

Around 1770, there were far more ponds on Clapham Common, some natural, some

created by gravel digging. Most have now gone. It is widely believed that Franklin experimented on the Mount Pond, but that cannot be established for certain.

Franklin repeated the experiment many times elsewhere. He measured carefully how far the oil would spread, and the experiment was an important step in the science of molecular chemistry, though Franklin himself did not grasp its full significance.

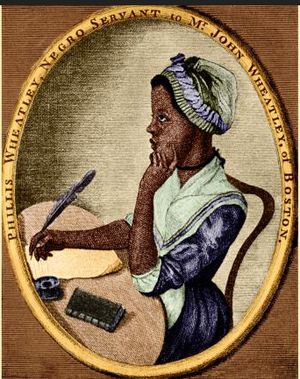

Phillis Wheatley

The other American visitor could not have been more different. Phillis Wheatley was a young African-American slave. Transported from Gambia to Boston, Massachusetts, aged only seven or eight, she was bought by John and Susanna Wheatley to be their domestic servant. She was treated more as a member of the family than a slave, and came to share their deep religious devotion. Well educated, she wrote poems, often on religious subjects. One of them, written when she was about twelve, was an elegy on the death of George Whitefield, the celebrated preacher. It was published to much acclaim, and as a result Phillis corresponded with many religious leaders, in Britain as well as America.

Among them was John Thornton, a wealthy merchant living on Clapham Common South Side in a house on the site of the Notre Dame Estate. He was a generous supporter of religious causes, and financed many in America through his friends the Wheatleys.

In 1773, aged nineteen, Phillis travelled to England. This was partly for the sake of her health, but also to get a book of her poems published (printers in Boston would not handle it).

While she was in London, Phillis stayed for a week with the Thorntons. “Please to give my best respects to Mrs and Miss Thornton” she wrote later, “and masters Henry and Robert who held with me a long conversation on many subjects”. Thornton himself was impressed by both her natural talent and her learning: “she is indeed a prodigy” he wrote. Accomplished in English, she also knew some Latin.

Another person she met in London was Granville Sharp, who showed her round the Tower of London. It was just a year since Sharp had won the great legal judgment in Somersett’s case, which rendered slavery unenforceable in England.

After less than two months, however, her visit was cut short by the news that Susannah Wheatley was dangerously ill. Phillis felt obliged to return, though she first took the step of getting a signed agreement that she would be given her freedom. Soon after her return her book was published – the first ever book to be published by an African-American.

She continued to correspond with Thornton. In 1774, he put to her a proposal that she and other African-Americans should return to Africa as missionaries. She firmly rejected the idea; as she put it, she would seem like a barbarian to the native Africans, whose languages she could not speak. She saw her destiny to remain in America. When the War of Independence broke out, she backed those fighting for independence, while castigating their support of slavery.

Her later years were unhappy. She continued to write poetry, but could not find a publisher for another volume. She died in poverty aged only 31. As she once wrote to Thornton, “the world is a severe schoolmaster.”