The Clapham Society Local History Series — 26

Clapham involvement in the Slave Trade

by Timothy Walker

This article first appeared in the South London Press on 14 July 2017

(Entitled: ‘Clapham Resident kept servant as a slave at home’)

It is well known that the Clapham Sect played a key part in bringing the slave trade to an end. What is much less well known is the involvement of Clapham residents in the slave trade both as customers in the West Indies and as suppliers.

From 1630 affluent puritan merchants acquired a house in Clapham to escape the noise, smells, and disease of the City of London. Although trading with most parts of the world, many of them concentrated on North America through their puritan connections and with Virginia and the West Indies. They imported sugar and tobacco, paid for by exporting provisions and slaves. Clapham residents John Brett and Richard Cranley helped to start the slave trade including supplying their neighbours and absent plantation owners, John Gould and Thomas Frere. Their views of slaves are clear from their wills, one left a legacy of ‘plantations, negroes, cattle, stock…’and another his ‘eighth share of plantation, stock of negroes, utensils and other appurtenances.’

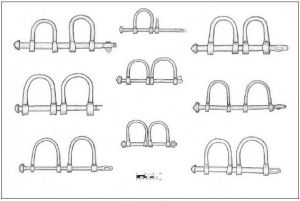

The slave traders needed goods to pay for the slaves in Africa, and a frequent choice was iron, often sourced from Sweden. Members of the Royal Africa Company were very active in this three way trade, bringing back sugar or tobacco to England. Clapham residents played an important part in this; Urban Hall, who had been a factor in Stockholm for many years held one or other of the two top posts in the Company for many years and his neighbour John Cooke was on its Board for twenty years. Their Clapham colleague, Anthony Tournay, exported almost £4000 worth of iron to Africa, enough to purchase up to one thousand slaves. Salvage from the wreck of one of his ships demonstrates that he also supplied the iron bilboes used to shackle the slaves during their transhipment to the West Indies.

Another Clapham resident kept a slave as a servant in England. He ran away, was recaptured trying to return to Guinea, but ran away again, and The Post Boy advertised for his return:

Run away … a black Boy named Lewis, about 16 years old, with a Hat on, in a darkish fine Cloth Coat lin’d with Red, without a Waistcoat, Leather Breeches and Blue Stockings: he speaks English very well. He has already been advertis’d of and … was brought home from Her Majesties Ship the Roebuck at Sheerness, aboarde of which he had continued several days, attempting to enter himself, having change’d his name to Scipio. He is now supposed to be Aboard some Man of War. Whoever secures him and gives notice of, or sends him to the said Dormer Sheppard shall have their charges paid and a Guinea Reward. Masters of Ships, and all other persons are forbid to harbour him at their peril.

The Clapham connection with slave trading continued through the eighteenth century and well into the nineteenth and, as a result, not everyone shared the Sect’s views on the slave trade. William Vassall, who owned plantations in Jamaica and had been expelled from Boston after American Independence, lived virtually next door to Wilberforce for five years. His letters contain many references to Wilberforce’s attempts to ban the slave trade, and he continually assured his correspondents in the 1790s that ‘Most people that I converse with think that the trade will not be abolished.’ At an early stage, however, he gave instructions ‘to buy more negroes now’ as a precaution.

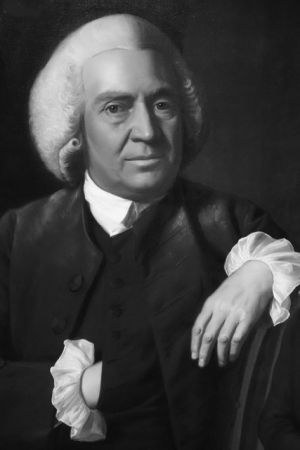

George Hibbert, a leading member of the proslavery lobby who later led the Parliamentary opposition to Wilberforce, lived close by in a house on North Side, Clapham Common. He was Agent for Jamaica, Chairman of the Society of West India Merchants, and was closely involved in the construction of the West India Docks on the Isle of Dogs. He gave evidence to Parliament in 1790 supporting the slave trade and making claims for compensation, and his speeches to Parliament in 1807 during the slave trade debates were later published.

Further evidence of Clapham slavery connections comes from the diary of one young man, a minister’s son from Scotland and future Lord Chancellor. He was profoundly unsatisfied by the very liberal and unserious world of the West Indies merchants in Clapham, where he was acting as a tutor. He found it ‘very irksome and it became more and more unbearable … The company frequenting the house consisted chiefly of West India merchants and East India captains, and the conversation turned on the price of sugars, the rate of freights, and the trifling gossip of the day.’

It is ironic that the village whose residents played such an important part in abolishing the slave trade, also provided a number of those who helped to start it over a hundred and fifty years earlier.