The Clapham Society Green Plaques

6. Clapham Library

Pictures relating to this history are at the foot of the page

1887-89: Clapham builds a Library

1887-89: Clapham builds a Library

Public lending and reference libraries are a nineteenth century phenomenon. In the early years of the century they were either subscription libraries or free philanthropic libraries. In the 1880s, Clapham had one of each sort, a subscription library in Studley Road and a poorly used free library at St Anne’s House, a working men’s club in Old Town.

Libraries paid for by local taxation were first authorised by an Act of Parliament in 1850. The Act allowed local authorities to set up free libraries, provided there was local poll, with two-thirds of the votes in favour. At first the new powers were almost entirely used outside London; a part of Westminster had a library as early as 1857, but the London parish authorities generally remained resistant until the mid-1880s. Wandsworth (the old parish, not the borough) was first off the mark, opening its library in 1885, closely followed by Battersea. Then the pace increased: Clapham Library was among ten new library administrations set up in 1887, a sudden upsurge which may have been as much the result of competitive civic pride as any new-found urge for learning.

In Clapham, the initiative came from the Revd George Forrester, Vicar of St Paul’s Church, Henry Bulcraig, a Churchwarden of Holy Trinity Church, and an anonymous friend of the Vicar, who offered £2,000, a very substantial figure at that time. The identity of the donor emerged only after his death in 1891: he was William A Guesdon, an Englishman who had made a fortune in Tasmania, probably in land speculations, and in old age had retired to Clapham. After a public meeting, a local referendum was held in the spring of 1887. Doubtless aided by the anonymous £2,000, the vote passed by a large majority, and a Library Commission was set up to carry through the work. Further fundraising followed, a public meeting in November 1888 raising £250.

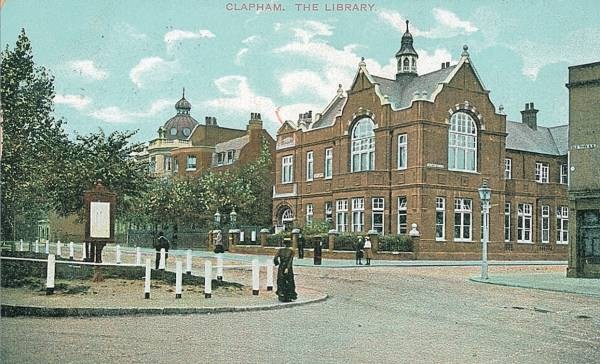

By that time a site had been chosen, not without intense local argument, which the local paper described as ‘the battle of the sites’. This was on the north side of the Common, at the junction with Orlando Road, on land to be purchased from the Lord of the Manor. The acceptance of this particular site gave rise to suspicions about the close links between some of the Commissioners and the manorial family, no doubt intensified when the chosen architect turned out to be the Surveyor to the manorial estate. A local resident wrote to the Chairman of the newly formed London County Council, asking him to put a stop to ‘another case of Clapham parish jobbery’.

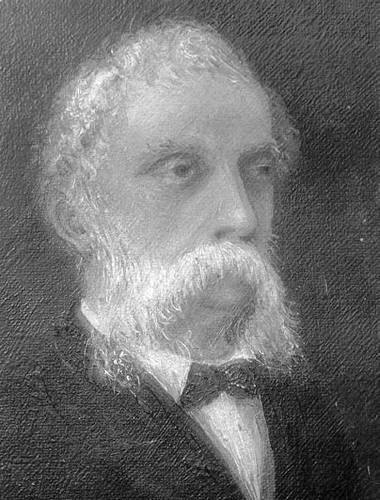

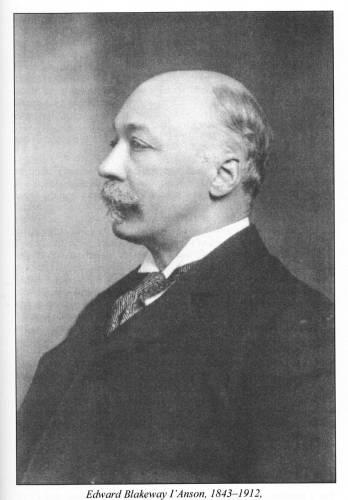

Whether or not there was any underhand dealing, both the site and the architect were good choices. The latter had been selected after a competition, for which six architects had been invited to submit designs. As usual with such competitions the designs were submitted under pseudonyms, though the assessors could probably have a made a good guess at which design was by whom. The winner was Edward Blakeway I’Anson (1843-1912), a respected City of London architect and surveyor who had grown up in Clapham. The builder was the local firm of Charles Kynoch and Co, and the cost, including purchase of the land, £3,865. Another £1,000 was spent on fittings and furniture. The Library was opened on 31 October 1889 by Sir John Lubbock, Vice-chairman of the London County Council, and an enthusiastic advocate of free libraries.

The Library in its first years

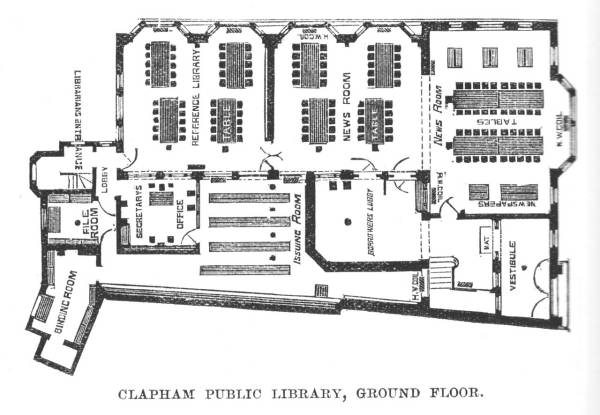

Externally, the Library is little different from its original appearance, but the interior reflected a quite different pattern of usage from public libraries of the present day. Beyond the entrance hall was the borrowing area, the public being separated from the bookshelves by a counter, over which the books were issued. To know what books were available, the public had to consult a catalogue; but in 1891 an open bookcase was set up, one of the first experiments with open access in London.

There was room in the issuing area for 27,000 volumes, though the initial stock was only 4,800. While every form of literature was included, there was special emphasis on the standard works on technical subjects – the Rector of Holy Trinity had consulted a range of craftsmen to find what books would be of the greatest practical use.

The room at the front with the bay window, and the whole of the space on the Orlando Road side of the building, was for reading newspapers, journals and works of reference. There were tables and chairs for 150 readers, with newsstands for the periodicals, all of polished oak. The number of publications was impressive – 16 daily papers, over 100 weekly, monthly or quarterlies, as well as 18 railway guides and timetables. This area was very well used, typically by working men during their dinner hour, and by shop assistants in the evening.

Upstairs, there was a large room, described in one account of the opening as being for public meetings and in another as ‘devoted to the purposes of a museum’. If the latter is correct, there is no information on what it contained. The Vestry (the local council which preceded the Metropolitan Boroughs) met there. At the back of the first floor was a flat for the Librarian.

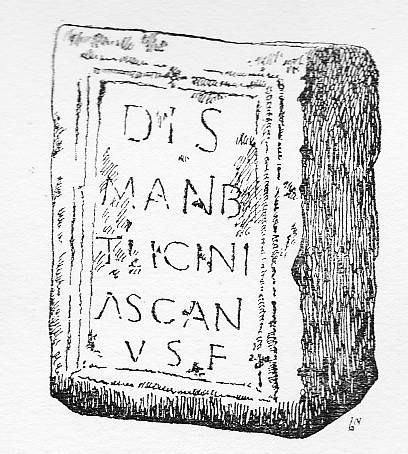

A Roman Stone

In 1911, a Roman memorial stone was given to the Library, where it now stands in the forecourt. It has a curious history. It had been found in 1777 in the foundations of a building in the Tower of London. How, when and why it came to Clapham is not known; but it was discovered in the grounds of Cavendish House on South Side, when that house was being demolished and the site developed. The developer, EJ Golds, a member of Wandsworth Borough Council, presented the stone to the Library. The Latin inscription is now almost illegible: but it translates as: ‘To the spirits of the departed and of Titus Licinius Ascanius; he made this for himself in his lifetime.’

Later history of the library

The original pattern of usage gradually changed, with borrowing becoming the prime function and most books on open access. In 1933-34, 279,246 books were issued, and in 1947-8 the figures were 249,286 in the Lending Department and 25,286 in the Reference Department.

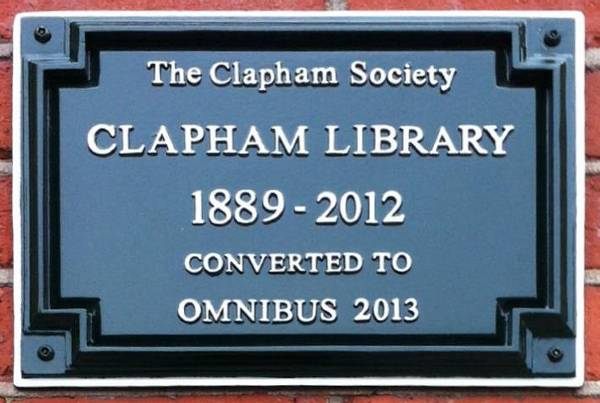

By the end of the 20th century, there were further changes. Reference books were now mainly kept at a central library at Brixton, while at Clapham Library records and CDs became available, and there were a few computers. But the old building was becoming less and suited to the functions of a modern library; so as part of a major development plan for leisure services in Clapham, Lambeth Council decided to move to a new purpose-built library in Clapham High Street. Despite protestations from many who were fond of the old building, the old Library closed in 2012.

The decision to relocate to a new building left the old library facing an uncertain future. It could simply have been sold to the highest bidder for whatever commercial development the new owner saw fit. But a vigorous and sustained local campaign resulted in Lambeth granting a long lease to Omnibus, a trust set up to use the Library as an Arts Centre. On 31 October 2014, the 125th anniversary of the opening of the Library was celebrated by a large gathering of supporters of Omnibus, including Sir John Lubbock’s grandson Lord Avebury.

The diagram of the original floor layout is taken from T Greenwood, Public Libraries, London 1891.

The Society is grateful to Finbarr Finnerty for access to his research on William Guesdon and related matters. In particular, we are especially grateful to him for his in-depth research which identified the anonymous donor whose name had eluded all previous researchers.

The Clapham Society Green Plaque was unveiled by Geraldine James on 31 October 2014, the 125th anniversary of the opening of the library.

Please wait for the gallery to load (9 pictures), it may take several seconds.