The Clapham Society Local History Series — 11

The Bonds of Clapham

by Joan Bond Barrett

Canadian family researcher Joan Bond Barrett unearthed family roots in 18th century Clapham while writing a history of her Bond family. The following is drawn from material in her manuscript The Bond Inheritance which traces the family through centuries of English history. It reveals a complicated network of family connections with Clapham, and the fact that her ancestor was the builder of Eagle House on Clapham Common South Side which bears a Clapham Society Green Plaque. Plaque article No 2.) Joan’s great-grandfather was George Bond who appears at the end of this story.

(The Bonds of Clapham Chart helps to identify the various members of the Bond family, many of whom are called Benjamin)

Please click here to see the Chart in a new window.

The illustrations: Please click on thumbnail to see a larger version.

Three of the five children of Benjamin Bond, a wealthy, 18th century London Turkey Merchant, moved to Clapham away from the smoke and dirt of London. Benjamin Junior and his sisters Catherine and Elizabeth were the first of three generations of Bonds to reside in the area. Benjamin Junior was a partner in his father’s trading company. Two hundred years earlier East Indian traders of the Levant Company had first introduced merchandise from Turkey to England and from then on, importers of various exotic wares became known as Turkey Merchants. Benjamin Junior was probably a less astute businessman than his father, for he wrote a codicil to his will in 1762 in which he stated:

‘I Benjamin Bond Jnr. now believe that I am not worth so much by many thousand pounds as what I was worth when I made the annexed will. To my father, brothers George and John Bond ten pounds each for mourning and to my two sisters, Catherine Bond and Elizabeth Brooksbank, ten pounds each for mourning instead of the sums left them before. (i) ’

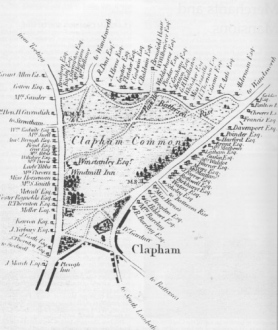

Sinclair Johnston

The next year his father died, then in 1770 his mother, Catherine Corbett Bond. Benjamin’s financial affairs looked up. His marriage had brought him an heiress, Elizabeth Hopkins, the daughter of John Hopkins of Hornchurch, Essex. John had inherited a fortune from his unmarried cousin, a London speculator at the time of the South Sea Bubble – another John Hopkins, nicknamed ‘Vulture’ in the press. Elizabeth became one of the benefactors of her father’s estate, and Benjamin now had the funds to build his dream home on land he leased from the Hankey family. Benjamin Bond Junior (1719-1783), the oldest in his family, was not the first brother to acquire an out-of-town retreat, but he was the only one to have a new house built to order. In early 1772 Eagle House appeared on Clapham Common South Side. (Fig.1)

Eighteenth century Clapham with its tolerant religious community attracted Nonconformists like these London Bonds. Over the years the family had added to their growing wealth through astute property investments, business deals and carefully arranged marriages with like-minded Presbyterian families with fortunes of their own. Babies were christened at the King’s Weigh House or at Dr. William’s Library in London – marriages took place in Anglican churches.

For more than ten years Benjamin and Elizabeth enjoyed life in their new home. They knew friends, relatives and business associates who also had residences around the Common. Correspondence telling something of their life and times is found in a collection of letters (ii) pertaining to the Chamberlaine family. One of the letter writers was Richard Chamberlaine whose sister Elizabeth had married Benjamin and Elizabeth’s son, the third called Benjamin in this line alone. Richard wrote from Chester in November of 1772 giving a word glimpse of the new Eagle House.

‘Mr. Bond’s father lives about a mile off in a noble house as strong as a castle, costing nearly £20,000. The richness of the furniture is past description. I was frequently entertained here and passed the Winter Evenings most agreeably with himself and his sister (Catherine), who is really good-natured and fond of me on my sister’s account whom they all loved.’

Unmarried Catherine (1724-1806) had been her mother’s companion and continued to live in Eagle House after both parents died. She was one of the most devout in her family leaving generous bequests to several widows and daughters of dissenting ministers and to Mr. Urwick of Clapham who had preached in the Protestant Dissenting Church there for 26 years. (iii)

Not only had the third Benjamin (1746-1794) later known as Benjamin Bond Hopkins (see below) married Richard Chamberlaine’s sister, but his own sister Elizabeth (b.1751) then married Richard’s brother George Chamberlaine on July 17, 1777, in St. Mary’s Church in Wimbledon. Witnesses to the marriage were her cousin Catherine Brooksbank and Benjamin. The newlyweds lived at Devonshire Place in London and had a country home, Burwood, in Cobham.

The mother of Catherine Brooksbank was Elizabeth Bond (1727-1810), the youngest child of the old Turkey Merchant. Catherine’s father was Joseph Brooksbank (1725-1759). Their children Catherine and Benjamin grew up in Clapham when their widowed mother married William Snell seven years after their father’s death. They moved to his home on Clapham Common South Side – two houses away from Eagle House. The Snell residence was next door to that of the Esdailes who were connected on the Hopkins side of the family. William Snell, an attorney, was a director of the Bank of England from 1772 to 1789 and was also a director of the East India Company. Like the Brooksbanks, Esdailes and the Bonds, the Snells were also Nonconformists. (Fig. 2)

Catherine Brooksbank (ca.1753-1841), who brought a fortune with her from her late father, married Thomas Page at Holy Trinity Clapham in 1781. He, too, was from Presbyterian roots. The trustees of the bride were Benjamin Bond Hopkins, her brother Benjamin and George Chamberlaine. Thomas Page’s manor Poynters at Cobham provided the bride with a marriage settlement of 200 acres. The Duke of York and other members of the Royal family visited them on several occasions.

Catherine’s brother Benjamin Brooksbank (1757-1842) married Philippa Clitheroe (1759-1849) the following year. From Philippa’s diary, which covered a period of 50 years, much is learned about these family relationships and society of the day. After the wedding she wrote:

‘March 8th we went to Mrs. Snell’s at Clapham to be introduced to a large formal party of relations. A grand dinner given. I felt all in a fright. We slept there, went to Town the next day, went to Boston to see my Beloved family. Staid 3 nights then home to Hatchford – my next pleasure was riding to Boston. Staid again 3 nights – on the 23rd, Mr. Bond Hopkins came to dinner, staid Sunday with us – A cousin of my husbands.’

What was striking about the diary is the amount of time whole families spent visiting, often staying weeks at each others’ homes. One spring in 1807 the Brooksbanks spent five weeks in Clapham. The other odd thing was that the only people whose first names Philippa mentioned were those of her children and people who shared a common surname. Even her ‘dear husband’ was Mr. B:

‘Apr. 2, 1782 – Mrs. Page brought Mr. and Mrs. Chamberlain to see us. The Bakers arrived from Town. Staid 2 nights. We returned to Town with them and staid a few days. Returned home on the 11th with Bonds at Wimbleton.’

She recorded her mother-in-law’s death after receiving a ‘bad account’ a few days previously:

‘Oct.29,1810 – We set out at 2 o’clock in the morning with my dear Husband and Martha. Travelled in a hack chaise all night and got to Clapham at nine in the morning of 30th. Found dear Mrs. S. alive just to know us and the good old lady expired the next morning. We found Mrs. Page and dtr at Clapham. Mr. Hood sent for immediately – he staid dinner.’ (iv)

Benjamin Bond Hopkins was the only son of the Bonds of Eagle House. As executor, he signed the codicil of a will of one of his ancient Corbett aunts giving his address as Clapham in 1771. When the will was probated in February of 1773, he signed his name not as Benjamin Bond Jr., but as Benjamin Bond Hopkins. He was the only male descendant of his grandfather John Hopkins who died on 15 November 1772. In order to secure his inheritance, within a matter of weeks he changed his name to Benjamin Bond Hopkins. He then purchased Painshill in Cobham which lay close to both George Chamberlaine’s estate and Poynters and commissioned the building of a new home.(Fig. 3)

Richard Chamberlaine wrote a letter just days before Benjamin’s grandfather died. It provides a picture of his brother-in-law’s lifestyle even before the inheritance:

‘I was treated most kindly by Mr. Bond when in London & by all the family. . . On Sundays he is very strict and reticent, reads prayers at night to all his servants, who are expected to be present. At other times he is as familiar and pleasant as other people. I had as much attention during his absence from home as if he was present. Two men servants constantly waited at table & the usual dessert with wine and fruits after dinner were all in princely style.’ (v)

The youngest son of the old Turkey Merchant was John (1730-1801) who had started out in his father’s import business. Late in life in 1792 John opened his own bank, John Bond & Son in Baker’s Coffee House in London’s Change Alley (vi). He and his wife Sarah Cowley (1739-1819) leased Eagle House in Mitcham as their country home in 1766. John and Sarah had three sons and three daughters who grew to adulthood. Their oldest son was named Benjamin, their youngest, Joseph, both of whom acquired homes in Clapham. Their children would be the third generation of young Bonds to grow up there.

John’s son Benjamin (1765-1834) became his father’s partner in the Bond bank having started out in the family importation business like all the Bond boys. He married Mary Ames Olive in Holy Trinity Church in Clapham on 17 February 1795. The assistant minister at the service was his cousin, Charles Frederick Bond, his uncle George Bond’s son. Mary Olive’s family also lived in Clapham. Benjamin kept a London residence at Devonshire Place plus a home at Clapham Terrace. The couple had two children, Benjamin born in 1796 who died young, and a daughter Mary born in 1797. Mary married the Rev. Thomas Robinson Welch of Hailsham, Sussex, on her birthday in 1833 in St. Marylebone.

Benjamin the banker remarried after his first wife died. His second wife was Elizabeth Shaw (1777-1867), and they had two sons, William Shaw (1802-1846) and Charles John (1806-1830). Benjamin’s youngest brother Joseph had become a partner in the Bond bank around the turn of the century. A few years later, their cashier Stephen Pattisall joined the partnership, and the name changed to John Bond, Sons & Pattisall. The bank was successful until an announcement appeared in The Times on March 29, 1831, that it had stopped payment on dividends. This was the beginning of bankruptcy proceedings which stretched over ten years. Benjamin had managed to keep paying dividends by selling off most of his own property, however, he passed away long before the final settlement. (Fig.4)

Mr. Pattisall carried on dealing with the court and the creditors. Joseph, meanwhile, had been living in France for years. His part in the bank’s failure remains a mystery. Even stranger is that Benjamin’s widow sent regular remittances to two of Joseph’s sons in Canada from 1850 until her death. These were George and Frederick, who became identified as ‘remittance men’ who did not work for a living. George named his last child William Shaw in honour of his cousin.

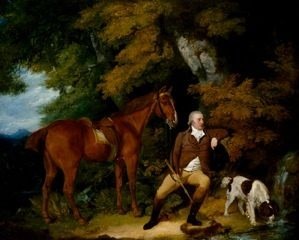

Philip Mould & Company

Joseph (1752-1854) and his wife Eliza Finch Mills (1776-1826) played a part in Clapham history supplying mystery, scandal and gossip about a family experiencing bad times. Joseph appeared to have made an extremely ‘good’ marriage. Eliza Finch was the daughter of Sir Thomas Mills (Fig. 5) and Elizabeth Moffatt. Eliza’s grandfather, Andrew Moffatt, owned ships which sailed for the East India Company. Her aunt was the Countess Dowager of Elgin, governess of Princess Charlotte Augusta and mother of the 7th Earl who brought the Greek marbles to England’s shores. They and Sir Thomas Mills were people whose names appeared in society columns of their day with more fiction than truth. (Fig. 6)

‘Jan. 2, 1785. – Lady Mills, altho’ she has lost an eye, a cheek, a side and a leg to palsy, yet she went off with her footman to France. She is the wife of Sir Thomas Mills in India, a natural son of the Pretender by the sister of Lord Mansfield.’(vii)

Scandal hung over the head of Sir Thomas as the illegitimate son, or nephew, of William Murray, Lord Mansfield. He was England’s Chancellor of the Exchequer, Lord Chief Justice of the King’s Bench and Attorney General for England and Wales. Sir Thomas was noted for his ‘arrogance and complete lack of integrity.’ The man was a favourite of Lord and Lady Mansfield throughout his life, an intimate of their circle and sponsored by Lord Mansfield with political appointments and endless opportunities for advancement and financial support. Sir Thomas was appointed Receiver General of Quebec where he robbed the country blind as tax collector, was recalled to England now and then to explain himself, then returned to his post. At his death in 1789, a bankrupt, he owed the government the equivalent in today’s currency of about £1,920,000. Lady Mansfield had been a sponsor at Eliza’s christening, hence the name Finch. Eliza’s mother Lady Mills was present at her wedding to Joseph in 1798 and would have been a visitor at her daughter’s home in Clapham. She would have known her grandchildren.

The couple’s London home was at 22 Edward St., Portman Square, but in 1810 Joseph also took a house on Clapham Common South Side near The Rookery. They had eight children who spent their childhood there: John Joseph Moffatt (1801- ca.1880), Eliza (1803-1858), Catherine (1804-1853), James Wilfred (1806-unknown), George (1810-1863), Sarah (1812-1886), Frederick (1815-unknown) and Francis Andrew (1818-unknown). The two youngest were born in Clapham. The children would have frequently seen their cousins who lived nearby.

Joseph ceased to be active in the bank. He had a long partnership with a Robert Nicholson and John Maitland operating as wool dealers until 1828 when the partnership dissolved with debts to be paid. If Eliza Finch had lived longer her children’s lives might have been different. She undoubtedly had played a hand at negotiating the marriage of her oldest son John Joseph Moffatt the year before her death. His first wife was Mary Charlotte Milnes Elmsley who had been born in Quebec in 1804 where her father had been the Chief Justice of Upper Canada and Speaker of the House. Eliza Finch had connections in high places. Then the Bond name came to smack of scandal. John Joseph Moffatt would marry four times, but the next wives lacked Mary Charlotte’s social standing.

Eliza Finch’s death in 1826 at Clapham Common devastated her husband, and he never re-married. He relied on his daughter Catherine who devoted her life to him. She mothered her youngest siblings – George, Sarah, Fred and Frank. The family continued to live in their Clapham home until the collapse of the Bond bank. An announcement appeared in The Times on the 30 April 1831, advertising the sale of contents of Joseph Bond, Esq. ‘removing from Clapham’ and several articles appeared about his bankruptcy. From time to time, John Joseph Moffatt took his younger brothers to live with his own growing family. Their father was living in Tours in 1840 when Sarah married. He and Catherine were living in St. Helier, Jersey, when the 1850 Census recorded him as an accountant, age 79. They were living in rented rooms in the home of the Governor’s Messenger and Lodging Housekeeper when Catherine died far away from the old home.

Once upon a time there was a family called Bond whose various members found happiness and a good life in Clapham, and then the good life for one branch was shattered. What happened to Joseph and Eliza Finch’s children? Eliza married Commander George Dobson of the Coast Guard in 1835 when she was already an old maid. James Wilfred landed in Debtors Prison at the age of 29 and lacked a permanent home according to the list the court provided of his past residences. Nonetheless, in 1840 he was admitted as an attorney in the Court of Queen’s Bench.

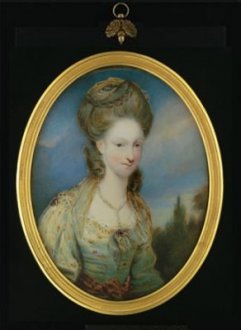

Private collection of Joan Bond Barrett

Sarah married her cousin, Henry George Hopkins, the son of Benjamin Bond Hopkins’s illegitimate son Henry. They lived a life of great wealth and comfort with many homes and many servants – but no children. Frank tried farming in Sussex but then disappeared leaving a wife and son. Fred and George emigrated to Canada around 1850. When Sarah died in 1886 she left Fred a £100 annuity. Remittance man George Bond lived as a landed gentleman in a rural community where everyone else worked for a living. He married a woman called Ellen Jane Elizabeth Street in the village of Lloydtown, Upper Canada, producing a family of his own. Curiously, Ellen’s father was Richard Finch Street.

I am grateful to Sinclair and Madeline Johnston, the present residents of Eagle House, Clapham Common South Side, for their hospitality while I was researching the Bond family in Clapham.

(i) Back Will of Benjamin Bond PROB 1/1103 (PCC Cornwallis 219) (pr 1783).

(ii) Back Kerr, John Bozman. Genealogical Notes of the Chamberlaine Family of Maryland. Baltimore, 1880, BiblioLife Reproduction Series, undated.

(iii) Back Will of Catherine Bond Prob. 11/1444 (Administration) June 6, 1806.

(iv) Back http://clanbarker.com/histories/Br/philippa/philippa.php.

(v) Back Kerr, John Bozman. Genealogical Notes of the Chamberlaine Family of Maryland. Baltimore, 1880, BiblioLife Reproduction Series, undated.

(vi) Back Price, F.G. Hilton. The Handbook of London Bankers. New York: Bart Franklin, 1876.

(vii) Back The M.S. Journal of Captain E. Thompson, R.N. 1783-85, Cornhill, Volume 17. London: Smith, Elder and Company, 1868.